|

Supplementary images not incuded in the book can be found here and animations with voice over can be found in the Multimedia section.  SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-2 .

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-2. The Southern sacred city of Hieraconpolis (Nekhen in Egyptian) was a place of pilgrimage for millennia, from pre-dynastic times until the end of pharaonic civilisation. Here we see a small percentage of the millions and millions of shards of pottery brought as offerings by pilgrims, who threw them to the ground and smashed them as sacrifices to the gods and to the ancestral spirits. There are probably more shards at Hieraconpolis than there are people in Egypt. SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-5 .

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-5. With Professor Joseph Davidovits (at left) discussing his theory that the blocks of which the main Giza pyramids were constructed were cast, not cut. Cast limestone concrete blocks cannot be differentiated from cut stone blocks by X-ray diffraction analysis, as the results for both are the same: both are limestone. Since the ancient Egyptians did not have cranes, they had no way of lifting huge stones into the air. To make the pyramids, it was merely necessary to carry disaggregated limestone rubble in sacks, pour this into moulds, add water, reed ashes, etc., stir vigourously, and cast a block, pounding it with wooden implements as it turned hard and cured. Then the mould was taken off and re-used. The blocks were cast directly on top of one another, which is why you ‘cannot fit a razor blade between them’. A thin layer of gypsum formed naturally between the cast blocks during the curing process, which gives the superficial appearance of mortar but is too thin to have been laid between cut stone blocks. Joseph has proved his theory by casting a four-ton block and a three-ton block in France, despite the bad weather. In Egypt, the climate was perfect for making pyramids in this way, since the sun and the heat made curing happen naturally, whereas rainy weather would have been an impediment. (Photo by Olivia Temple) SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-6 .

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-6. King Narmer wearing the white crown of the South, on the reverse side of the Narmer Palette. Two Delta Libyan captives are being rather badly treated. The one above is being held by the royal falcon, from whose chest a human arm protrudes, grasping a plaited rope. This rope does not enter the nose of the human face, as may casually appear to be the case. A close inspection shows that just beneath the beard is a noose made of the same rope round the man’s neck. The plants depicted are papyrus plants, which only grow in stationary non-flowing water, and never grew in the Nile. They are depicted as emerging from one of the countless papyrus swamp islands which filled the Nile Delta in those days, before it was drained in modern times for agricultural purposes. (A replica of the ancient Delta as a vast papyrus marsh still survives in Uganda at the head of the White Nile, and is still full of crocodiles and hippos and wild birds as the Delta once was.) SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-7 .

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-7. Detail of top of the obverse side of the Narmer Palette showing King Narmer (left) wearing the red crown of the north (which he has just conquered); his name in hieroglyphs is suspended in space directly in front of his head, and the sign at the top is believed to represent a catfish, so maybe he was a ‘Southern soul brother’. This name is also shown larger in the centre of the top register, with bits of a palace façade motif to either side of the bottom hieroglyph (believed to show a bull’s thigh). He is advancing towards the bound and decapitated bodies of ten of his northern enemies, whose heads with Libyan-style goatee beards lie between their feet. The four standard-bearers marching ahead of Narmer carry four standards, as follows: two standards showing Horus as a falcon sitting on his sacred ‘perch’ made of reed bundles (probably Horus of the North and Horus of the South), a sacred dog, probably Upwawet who as a pathfinder was a form of Anubis, and a uterus with trailing umbilical cord, presumably representing the king’s ka or ‘double’ who embodies his spiritual force. The person directly in front of the king is believed to be his sandal-bearer. SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-8 .

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 6-8. Detail of top of the obverse side of the Narmer Palette showing King Narmer (left) wearing the red crown of the north (which he has just conquered); his name in hieroglyphs is suspended in space directly in front of his head, and the sign at the top is believed to represent a catfish, so maybe he was a ‘Southern soul brother’. This name is also shown larger in the centre of the top register, with bits of a palace façade motif to either side of the bottom hieroglyph (believed to show a bull’s thigh). He is advancing towards the bound and decapitated bodies of ten of his northern enemies, whose heads with Libyan-style goatee beards lie between their feet. The four standard-bearers marching ahead of Narmer carry four standards, as follows: two standards showing Horus as a falcon sitting on his sacred ‘perch’ made of reed bundles (probably Horus of the North and Horus of the South), a sacred dog, probably Upwawet who as a pathfinder was a form of Anubis, and a uterus with trailing umbilical cord, presumably representing the king’s ka or ‘double’ who embodies his spiritual force. The person directly in front of the king is believed to be his sandal-bearer. FIGURE 36.

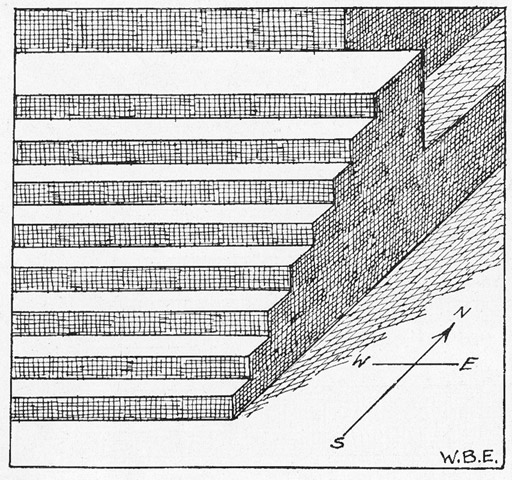

FIGURE 36. This cutaway diagram shows the steps of the excavated Step Pyramid tomb of King Enezib (or Anedjib), fifth king of the First Dynasty, which was discovered at Saqqara in 1937 by Emery and at first attributed to Nebetka, a royal official lived under Enezib’s reign. We see also in this drawing that the structure is oriented precisely to the cardinal points, as are the Giza pyramids. (Figure 64 from Walter B. Emery, ‘A Preliminary report on the Architecture of the Tomb of Nebetka’, Annales du Service, Cairo, Vol. 38). A fuller report on this tomb was published eleven years later in Walter B. Emery, Great Tombs of the First Dynasty, Volume I, Cairo, 1949, where this drawing is Figure 38-A on page 84, and the tomb has been numbered Tomb 3038. After some years of further debate and consideration, Emery decided that there might be ‘some more startling possibilities’ about this tomb than just belonging to a royal official. It was originally constructed as a stepped pyramid! The top was then cut off, and the pyramid form entirely concealed by a new superstructure in the conventional tomb form with a frontage of what is known as ‘the palace façade’ design. In 1961, Emery finally said what he thought this tomb really was; in his book Archaic Egypt, he said : ‘The building is dated to Enezib, and, although the name of an official called Nebitka occurs on jar-sealings, etc., it would appear probable that it is the burial place of the king.’ (page 82) See discussion in main text. FIGURE 37.

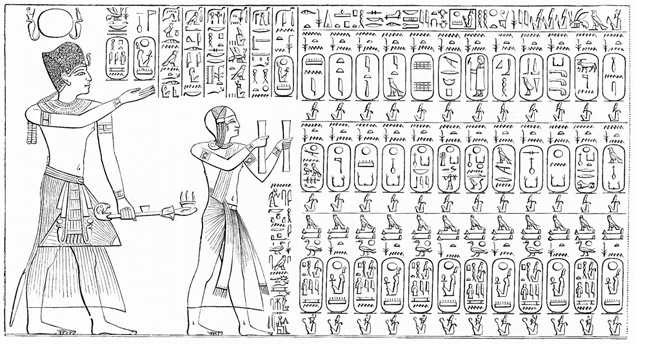

FIGURE 37. This is the famous ‘Tablet of the Kings; carved on a wall of a corridor in the Temple of Seti I at Abydos in Upper Egypt. Since it is impossible to photograph the carving face on, due to its width and the narrowness of the corridor, this engraving of it is invaluable. (It actually extends further to the right.) Seti I, second king of the 19th Dynasty, is seen making offerings (he holds an incense pipe in his left hand) to the spirits of the royal ancestors. He is preceded by a priest. This engraving was published in Sir Norman Lockyer’s The Dawn of Astronomy, London, 1894, p. 21. This king list is now generally known by the name of The Abydos King List. Each cartouche contains the name of an ancient king, whose spirits is being honoured. Heretical kings such as Akhenaten and his son Tutankhamun are omitted from this List, which was for ceremonial purposes, as their spirits must not be honoured. Seti I’s temple at Abydos was really a ‘Temple of the Royal Ancestors’ culminating in himself. One of its purposes was to strengthen his claims to legitimacy by portraying him as the direct successor of all the dead kings from earliest times. It is believed that he carried out elaborate ceremonies to honour the dead kings at least once a year in person. At that time, all of their names would have been recited aloud. FIGURE 38.

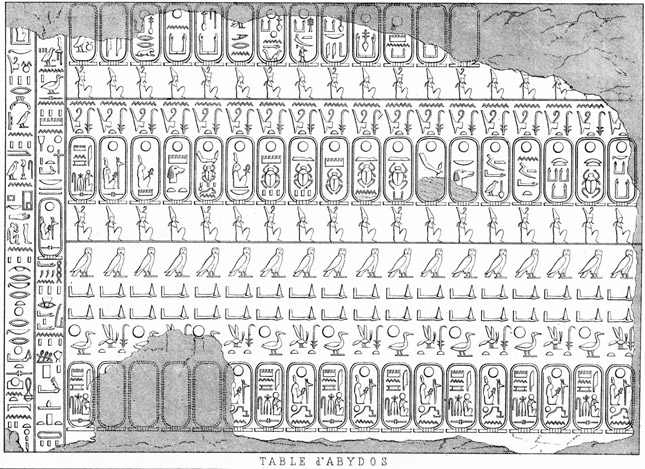

FIGURE 38. An illustration of part of the Abydos King List, carved on a wall of the Temple of the Ancestors of King Seti I, which is known today simply as ‘The Temple of Seti I’ at Abydos, north of Denderah in Upper Egypt. (From L’Égypte: Atlas Historique et Pittoresque, Plate I, date unknown, but late 19th century, a loose plate in the Collection of Robert Temple.) FIGURE 39.

FIGURE 39. An illustration of part of the Abydos King List, carved on a wall of the Temple of the Ancestors of King Seti I, which is known today simply as ‘The Temple of Seti I’ at Abydos, north of Denderah in Upper Egypt. (From L’Égypte: Atlas Historique et Pittoresque, Plate I, date unknown, but late 19th century, a loose plate in the Collection of Robert Temple.) FIGURE 40.

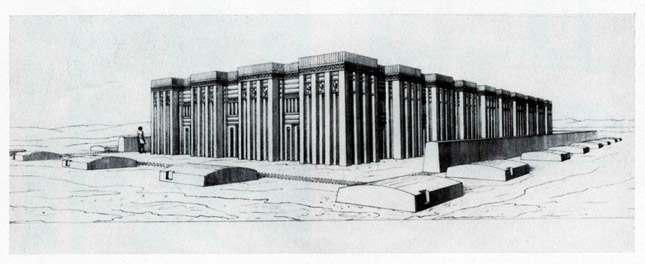

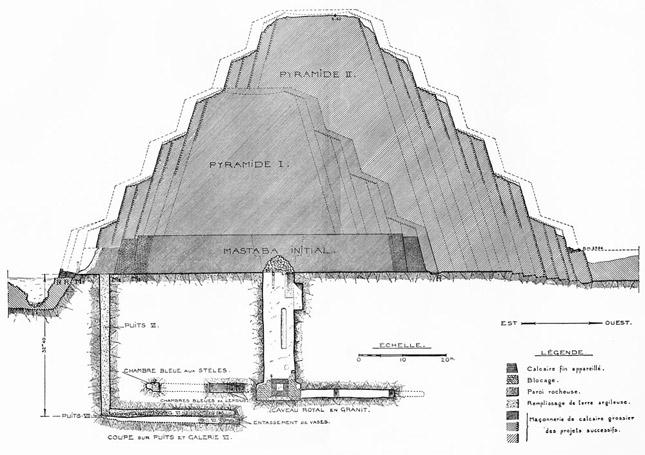

FIGURE 40. Jean-Philippe Lauer’s diagrammatic section of the Step Pyramid at Saqqara, showing in its shaded portions its three construction phases above ground level (below ground is shown as white). Phase One is the squat rectangular mastaba at the base, labelled ‘Initial Mastaba’. Phase Two is Pyramid 1. Phase Three is Pyramid 2, which is what we now see from the outside, secretly encasing the two earlier structures entirely. This was all done within the lifetime of King Zoser by his architect, Imhotep, and it was all done on purpose. The question is: why? Until now, it has been presumed, for want of any other explanation, that the pharaoh and his architect could not make up their minds, and that they first decided to build a mastaba, but were not satisfied with it, and then build a small pyramid on top of it. But then, dissatisfied still, they built yet another pyramid, much larger this time, which swallowed up both of the earlier structures (which were only discovered by Lauer’s probings and excavations). However, this explanation suggests that they were rather foolish and dithering, and does not fit psychologically somehow with what we know about Imhotep as reputedly the greatest individual genius in Egyptian history. But now a surprising alternative resents itself: perhaps Imhotep was making a definite ‘statement’ of a political and cultural nature. For what he did was precisely the opposite of what King Semerkhet of the First Dynasty did: Semerkhet decapitated his predecessor, King Enezib’s, pyramid at Saqqara and built two successive mastabas over it. Imhotep did the exact reverse, also at Saqqara, starting with a mastaba and then building two pyramids over it. This may have been intended to have, not only a political and cultural significance, but a magical significance as well: undoing the ‘bad magic’ of a previous age by reversing it with corrective ‘good magic’. See the further discussion in the main text. This drawing is folding Plate 11 in Jean Philippe Lauer, Histoire Monumentale des Pyramides d’Égypte (Monumental History of the Egyptian Pyramids), Volume I, Les Pyramides à Degrés (IIIe Dynastie) (The Step Pyramids of the Third Dynasty), Cairo, 1962. FIGURE 41.

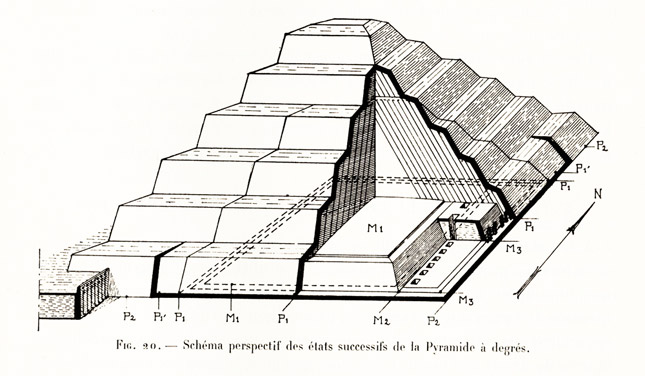

FIGURE 41. Schematic perspective view of the successive layers of the Step Pyramid [of Zoser at Saqqara]. Figure 20 on page 71 of Jean-Philippe Lauer, Histoire Monumentale des Pyramides d’Égypte (Monumental History of the Pyramids of Egypt), Volume I: Les Pyramides à Degrés (IIIe Dynastie) (The Step Pyramids (Third Dynasty)), Cairo, 1962. The rectangular and flat mastaba (‘M1’) was the first construction (slight modifications to it are labelled M2 and M3), the step pyramid labelled ‘P1’ was then built on top of it, and finally the Step Pyramid as we now see it (‘P2’) was in turn constructed on top of that. FIGURE 42.

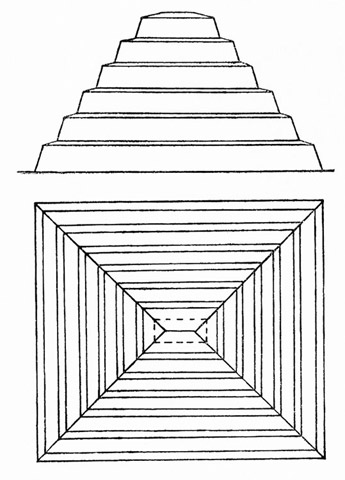

FIGURE 42. Elevation and plan of the Step Pyramid of Saqqara, as published by its chief excavator, Jean-Philippe Lauer. This is Figure 1 from Jean-Philippe Lauer’s early article, ‘Remarques sur les Monuments du Roi Zoser à Saqqarah’, Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Vol. XXX, 1930, page 334. Lauer stressed that the Step Pyramid was not square but rectangular in its plan. (The northern and southern sides are longer than the eastern and western sides, by a ratio of 6 to 5.4 at the base. This ratio changes as the structure gets higher and you move to higher levels or ‘steps’, so that the northern and southern sides grow longer and the eastern and western sides grow shorter the higher you go.) Elevation and plan of the Step Pyramid of Saqqara, as published by its chief excavator, Jean-Philippe Lauer. This is Figure 1 from Jean-Philippe Lauer’s early article, ‘Remarques sur les Monuments du Roi Zoser à Saqqarah’, Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Vol. XXX, 1930, page 334. Lauer stressed that the Step Pyramid was not square but rectangular in its plan. (The northern and southern sides are longer than the eastern and western sides, by a ratio of 6 to 5.4 at the base. This ratio changes as the structure gets higher and you move to higher levels or ‘steps’, so that the northern and southern sides grow longer and the eastern and western sides grow shorter the higher you go.) FIGURE 43.

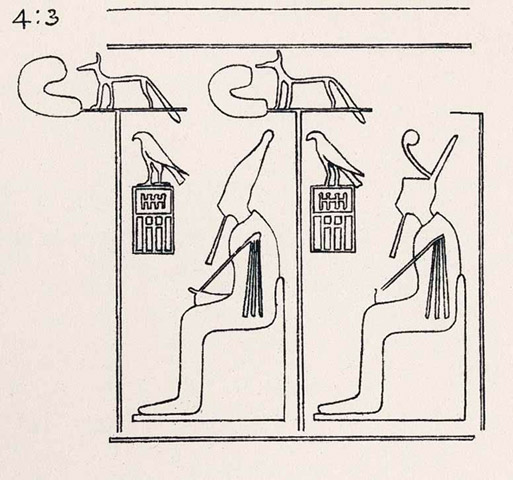

FIGURE 43. Image of a ‘unifier’ in his two guises, King Djer (also called Zer), second king of of the First Dynasty, shown twice on a jar sealing in his tomb, seated on his throne and holding his flail as a symbol of royal authority. At left, he wears the white crown of the South, and at right he wears the red crown of the North. In front of him, his name is contained beneath the feet of a falcon surmounting a design known as a serekh, which was the standard presentation for a king’s name at that period (later superceded by the cartouche). Standing in front of each image of Djer is a standard with a rampant jackal/wild dog at the top, representing either Upwawet (‘Opener of the Ways’), Khenti-Amentiu (Chief of the Westerners, the earliest name and jackal form of Osiris), or a form of Anubis (or some conception, no longer entirely clear to us, embodying all of the above ideas of deity). This illustration is from Figure 108 of Plate XV in Sir Flinders Petrie’s Royal Tombs of the Earliest Dynasties, 1901, Part II, Egypt Exploration Fund, London, 1901. FIGURE 44.

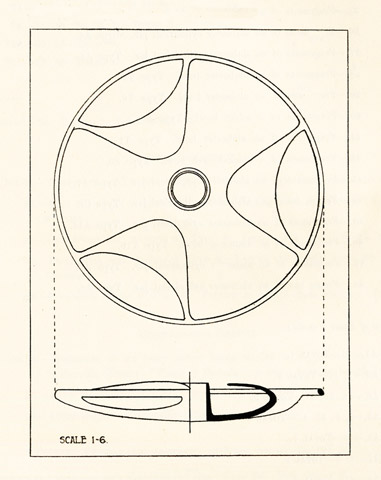

FIGURE 44. Walter Emery’s drawing in section and plan of the mysterious ‘schist bowl’ excavated by him from the First Dynasty Tomb of Sahu at Saqqara.(Figure 58 on page 101 of Walter B. Emery, Great Tombs of the First Dynasty, Volume I, Cairo, 1949.) FIGURE 45.

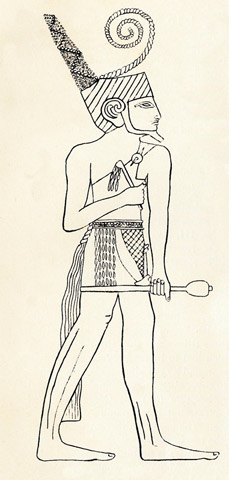

FIGURE 45. King Narmer, as depicted on the reverse side of the Narmer Palette, striding forth with a mace in his hand and wearing the Crown of the North (Lower Egypt), generally called ‘the red crown’, though in Old Kingdom times it was sometimes called ‘the green crown’. The coil emitted from the centre of the turban (which resembles a Fibonacci spiral in mathematics) can clearly be seen to be made of something twisted. Petrie thought it was ‘a piece of tightly twisted linen, and … it must have been made over a wire or other stiff foundation to keep it in position.’ (Ancient Egypt, June, 1926, Part II, pp. 36-7). Narmer, shown on the other side of the palette in smiting position and wearing the ‘white crown’ of the South (Upper Egypt), as seen in Plate 38 and Figure 46, was evidently a southern king who conquered (‘smote’) the North, since he did his smiting while wearing the southern crown, but progressed peacefully, evidently as a victor, wearing the northern crown, with his mace at rest. Whether Namer was ‘Menes’, or whether his son How-Aha was Menes, the Unification of Egypt by force took place from the south to the north, and resulted in the creation of what we call ‘The First Dynasty’. FIGURE 46.

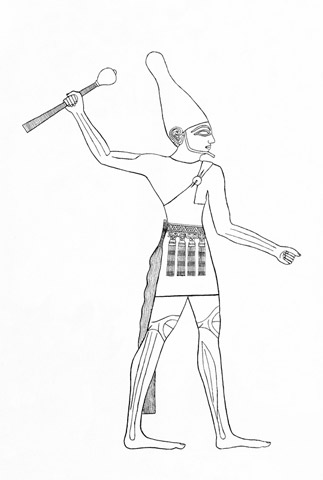

FIGURE 46. King Narmer smiting an enemy, drawn from the obverse side of the Narmer Palette, and showing the details of his costume and mace. FIGURE 47.

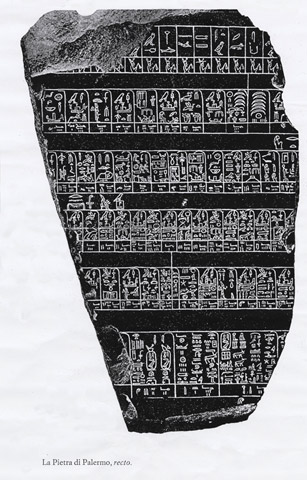

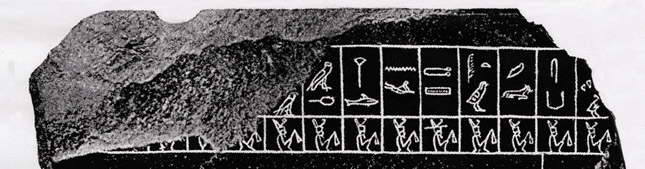

FIGURE 47. The Palermo Stone, obverse side. This image was given to me by the officials of the museum at Palermo, and has been digitally enhanced by Michael Lee. The top row, broken at left, lists the predynastic kings of the Delta in the north of Egypt (see Figure 49 for a closeup view of this row). FIGURE 48.

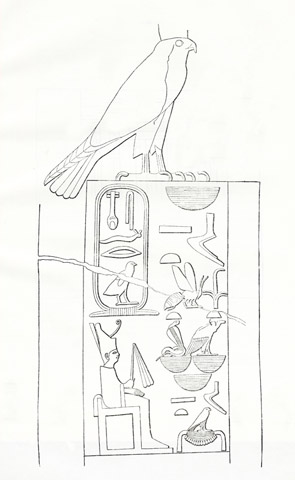

FIGURE 48. A carving found at Dashur of King Sneferu, the first king of the Fourth Dynasty and reputed father of Cheops, seated on his throne, holding the royal flail and wearing the joint crowns of the north and the south. His name is shown above him in its cartouche. To the right are the pairs of sedge and hornet, vulture and cobra, which represent ‘king of north and south’. The royal Horus falcon surmounts the inscription. FIGURE 49.

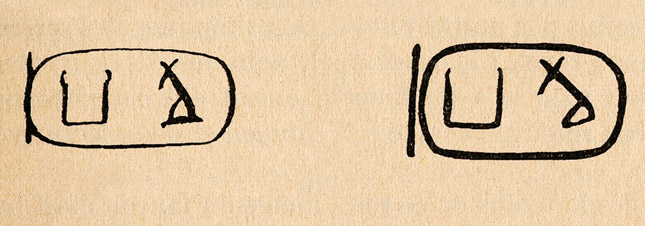

FIGURE 49. The top row of the Palermo Stone’s obverse side inscription. This shows a row of the names of a whole series of predynastic kings of Egypt, all wearing the red crown of Neith and of the North. The row is read from right to left. The seated king at the bottom of each box shows that the name written above it in hieroglyphs is that of a northern king. The first name is illegible except for the fact that it ends in ‘-u’ (or some suggest ‘-pu’), the vowel ‘u’ being written as a chick. The next name, and the first complete one, is Seka. The next is Khaiu, the next Tiu, the next Thesh or Tjesh, the next Neheb or Niheb, the next Uazanez or Wadj-adj, the next Meka or Mekhet, and the last broken one ends in ‘-a’. None of the names of these kings is recorded in or on any other surviving document or monument. They are all completely ‘unknown to Egyptology’. This is the only surviving evidence that they ever existed. Many scholars thus feel uncomfortable about them, and many have simply ignored this row of names and refuse to discuss them at all, I suppose lest they lose their appearance of omniscience and of being ‘experts’. But when there is a single piece of evidence about something and that is it, there are no experts, and everybody is equally ignorant, so there is no shame in that. If the stone were not broken, we can see clearly by counting the bottoms of the boxes that there were at least 13 kings named, the names of seven of which are wholly visible and two partially visible. I suggest that these ‘unknown kings’ ruled an important northern Egyptian kingdom extending across the Delta and at least as far south as Meidum (four hours’ drive by car south of Cairo today), but probably as far as Herakleopolis (somewhat further south, as discussed in Chapter 8). I believe these kings may have presided over the largely-vanished civilisation which was later conquered by the warlike southerners King Narmer and his son King Hor-Aha, creator of the ‘First Dynasty’ of a unified Egypt. Could this ‘lost kingdom’ have built the Giza pyramids, and had all trace of their existence erased by the pharaohs Cheops and Chephren when they ‘usurped’ them? (This image is taken from one given to me by the museum officials at Palermo, which was then digitally enhanced by Michael Lee.) FIGURE 50.

FIGURE 50. The name of King Neferka, a king believed to date from the Third Dynasty (but in any case definitely not later than that), copied out by Jean-Philippe Lauer from occurrences of the name which he found when he excavated the great shaft at Zawiyet el-Aryan. The name is shown in a royal cartouche, so is obviously that of a king. It is read from right to left, the second sign being the upraised arms which are read ‘ka’. No one is really certain what the sign on the right is meant to be. It has been suggested that it is an archaic hieroglyph for ‘giraffe’, which was called nefer. Others have suggested that it is a poorly drawn version of a different hieroglyph, which would mean that the name would be read Nebka, though I do not find that at all convincing. This king, who appears to have been the king who constructed the Zawiyet el-Aryan shaft, was certainly not a king of the Fourth Dynasty, the dynasty to which ‘pyramid tomb theorists’ would like to attribute it, whilst trying to maintain that it is an ‘unfinished pyramid’. In fact, it would have been physically impossible to construct a pyramid on top of such a vast shaft, which is the case also with the smaller but similar one at Abu Ruash, but lack of engineering knowledge rarely deters an inferior Egyptologist from pushing his pet theory when it suits him. See Plates X-X and Figures X-X in Chapter 3, where this shaft and its twin at Abu Ruash were discussed, and where I suggested that their purpose was for rectifying the calendar by carrying out precision observations of star culminations at the meridian (north-south) line. (The shafts are oriented precisely north-south.) |