|

Supplementary images not incuded in the book can be found here and animations with voice over can be found in the Multimedia section.  SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 5D .

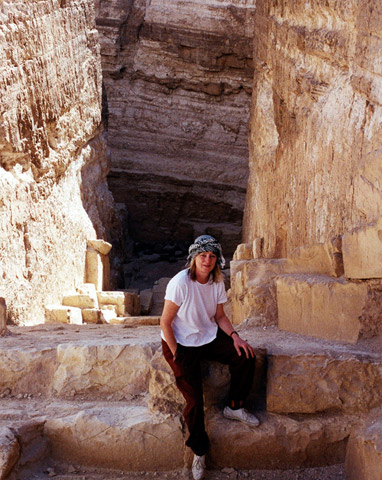

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 5D. Olivia Temple sitting at the top of the vast open shaft at Abu Ruash, six miles north of Giza on a hill. The shaft points due north and was in my opinion an astronomical observation shaft for stars crossing the meridian (the north-south line). Without such a shaft, the Egyptians could not have achieved sufficient accuracy with their calendar to be certain of the correct dates of all their religious festivals. (They did this by noting the precise moments when key stars crossed the meridian line in the sky by sighting up the shaft, known as ‘observing stars culminating at the meridian’ by astronomers.) A similar dilemma faced the Roman Catholic Church for centuries, and led to their adopting extraordinarily complex and expensive measures to use their vast churches in Italy and France (such as Saint Sulpice in Paris, as mentioned in The Da Vinci Code) for observing solar rays along brass meridian lines inlaid into the church floors, in order to be certain of the date of Easter. The idea, often suggested by people who have not thought the matter through, that a pyramid once stood on top of this shaft is ridiculous, as there was only a wall around the site (see Figure 10), never a pyramid. A ‘twin’ of this shaft exists also south of Giza at a place called Zawiyet el-Aryan, but it is inside a military base and no archaeologists are allowed to visit it. For old photos of it before the military base was constructed, see Plates 8 and 8B. The Zawiyet Shaft excavations revealed its association with a Third Dynasty pharaoh named Nebka, whereas the Abu Ruash Shaft has associations with a Fourth Dynasty pharaoh named Djedefre, who even built a mudbrick temple nearby, from the ruins of which a magnificent portrait bust of him was excavated. SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 8B .

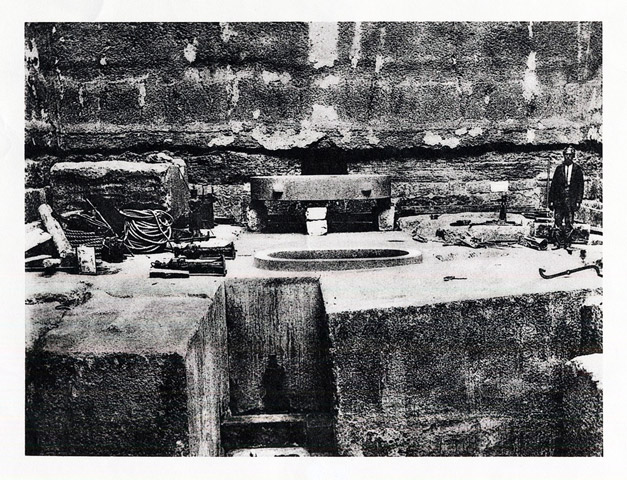

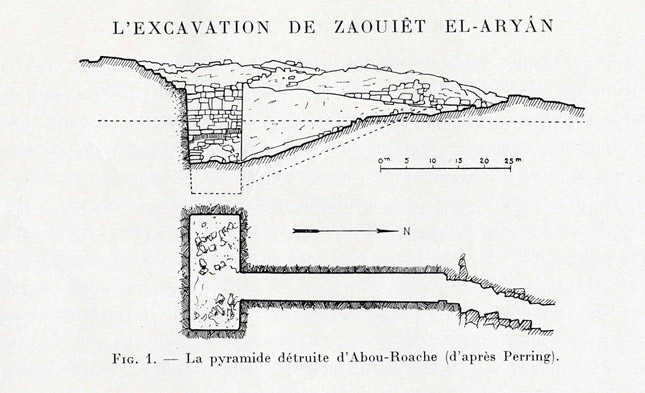

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 8B. The complicated granite platform or ‘base’ (radier, as Lauer calls it in French) at the bottom of the Zawiyet el-Aryan meridian observation shaft shown in Plate 8. The archaeologist Jean-Phillip Lauer stands at right, giving an indication of the scale. He has no explanation for the nature and purpose of this strange structure. I believe that the oval depression in the centre of this platform was the base for a giant water-clock, which was used to mark the hours of the night while the astronomical observations were taking place in the adjoining meridian observation shaft. The water clock, re-calibrated once a day during daylight hours by a shadow-clock, would have made possible a precise timing of each successive stellar ‘culmination’, since the daytime shadow-clocks could not be used for time-keeping at night. Only by timing every ‘culmination’ precisely could precise calendrical measurements be obtained. (Ancient Egyptian water clocks and shadow clocks survive, as well as texts describing their use, and we know exactly how they worked.) This is Plate 1-B from Jean-Philippe Lauer, ‘Sur l’Age et l’Attribution Possible de l’Excavation Monumentale de Zaouiet el-Aryan’ (Concerning the Age and the Possible Attribution of the Monumental Excavation of Zawiyet el-Aryan’), Revue d’Égyptologie, Tome 14, Paris, 1962, pp. 21-36 with additional plates page. SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 12c .

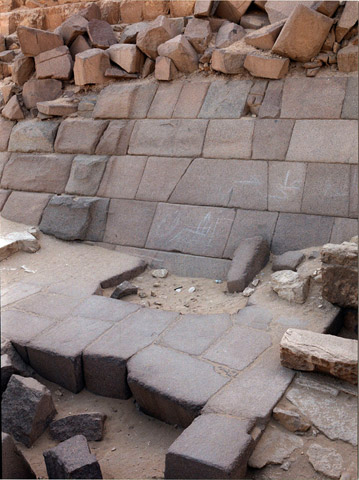

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE12C. A smooth portion of the eastern face of the Pyramid of Mycerinus, surrounded by rough portions. No one knows why the granite casing stones alternate in their outer surfaces in this manner, except that on the north face it signifies the location of the entrance. In the foreground here, the pavement of the Mycerinus Funerary Temple may be seen. Whereas the casing stones of the pyramid have no visible mortar between them, the paving stones of the temple are much cruder and have substantial amounts of mortar between them, suggesting that they were built by less skilled workmen than those who built the pyramid. The pavement is also clearly ‘shoved up against’ the pyramid at a later date, and this is done rather crudely. Because the pavements of the funerary temples of the other two main Giza pyramids do not survive at their western edge like this, we cannot see whether those also were ‘shoved up against’ the eastern faces of those two pyramids in a similar manner. However, if one of the three Giza funerary temples was demonstrably a later addition as this is, then this suggests that all three of them were, and this substantiates my suggestion that the pyramids were ‘usurped’ for funerary purposes by the later pharaohs Cheops, Chephren, and Mycerinus. SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 5G.

SUPPLEMENTARY PLATE 5G. The three pyramids of Giza seen through the Cairo smog from the top of the hill of Abu Ruash. It was on this hilltop far from Giza that Pharaoh Djedefre, who reigned circa 2581-2572 BC, between the reigns of Cheops and Chephren, was supposed to have built a large pyramid. However, no pyramid is actually there, and it is doubtful that any ever was. What is there is a gigantic excavation of the bedrock to form a mammoth descending passage and chamber, but these are exposed to the sky and seem never to have been covered over. Massive stones forming some sort of surrounding structure on the surface survive, and many are known to have been carried away. But it cannot be demonstrated that these ever constituted even the beginnings of an actual pyramid. Certainly if a pyramid were commenced here, it was never finished. The Abu Ruash ‘thing’, whatever it was, was certainly huge, but it is not certain what it actually was. Its supposed association with Djedefre is also established only through circumstantial evidence, and there is no direct evidence. I believe that the Abu Ruash site was a merdianal astronomical observation shaft, and that it was surrounded by a stone wall (see figure X). This photo gives the necessary perspective to show the relationship between the site and Giza, which lay 600 feet below and six miles away to the south. FIGURE 7.

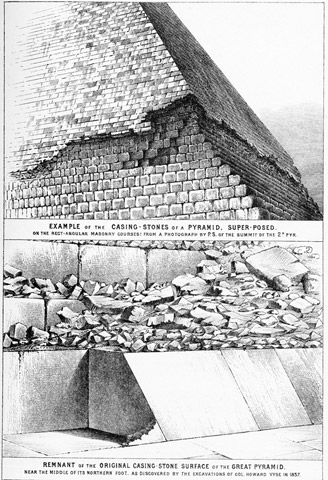

FIGURE 7. Here we see remaining casing stones of the two main Giza pyramids drawn clearly by Piazzi Smyth, to show what they were like. From Charles Piazzi Smyth, Life and Work at the Great Pyramid, Edinburgh, 1867, 3 vols., Volume II. FIGURE 8.

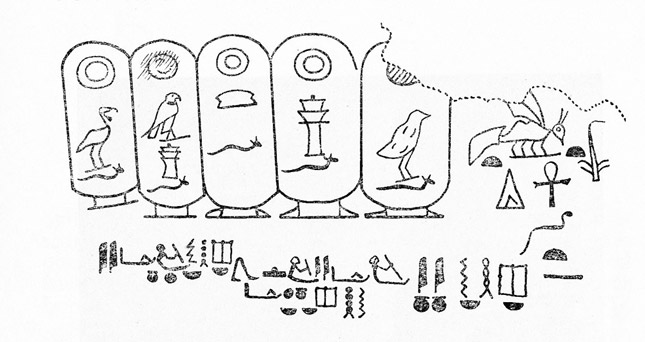

FIGURE 8. This is the ‘mini-king list’ of a succession of pharaohs of the 4th Dynasty found carved on a cliff at Wadi Hammamat in the Eastern Desert of Egypt, between the Nile and the Red Sea. The kings’ names go from right to left in historical sequence, and there are five of them, each in a royal cartouche. The first one, with the little chick, broken at the top, is the name of King Khufu, better known to us as King Cheops (the Greek version of his name). Next, to the left of him, is the name of King Radjedef, who is these days generally known as Djedefre. He was the first known pharaoh to incorporate the name of the sun god, Ra or Re, in his name. It is symbolised by the solar disc at the top, and the succeeding pharaohs to the left of him all used it as well. To the left of him is King Raqaf, these days generally known amongst Egyptologists as Khafre, and to the ordinary person as Chephren (the Greek version of his name). Egyptologists disagree amongst themselves as to whether the ‘Ra’ or ‘Re’ should really pronounced at the beginning of the name, as it is written, or whether it was only written there out of respect, and should really be pronounced at the end. The next king to the left is King Ra-Hordjedef, and the last on the left is King Ra-Biuf, or Biufre (the Greek version of his name being Bikheris). This important early list of kings was first discovered in 1949 by Fernand Debono. This list emphasises the fact that a little-known pharaoh intervened in the succession between Cheops and Chephren, and that two other pharaohs who are even less well known intervened between Chephren and Mycerinus, who is not even mentioned here. This evidence is awkward for those who advocate the theory that the three main pyramids of Giza were built by three kings in succession as their tombs, namely Cheops, Chephren, and Mycerinus. (from Etienne Drioton, ‘Une Liste de Rois de la IV Dynastie dans l’Ouadi Hammamat’, Bulletin de la Société Français d’Égyptologie, Number 16, October 1954, pp. 41-9.) FIGURE 9.

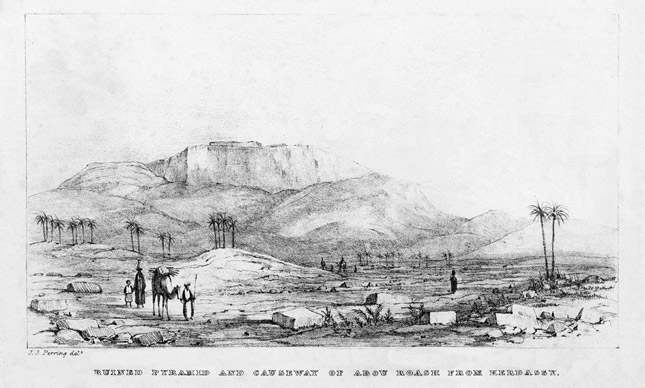

FIGURE 9. This drawing published by Vyse in 1840 shows the hill of Abu Ruash, which rises 60 feet above Giza to the north, and is the site of the so-called ‘unfinished pyramid’. It was however much more likely to have been an excellent site for an astronomical observation shaft. The hill was approached by a long and grand causeway, which would have been necessary for access by the priests and pharaohs of those days, with their entourages. Many Egyptologists have illogically assumed that the presence of a causeway proves the necessary presence of a pyramid. However, just because the Washington Monument and Big Ben are both beside roads does not mean that one cannot be a clock tower and the other a commemorative monument. I know of no rule of logic which demands that all structures approached by causeways are required to be pyramids. (This plate faces page 7 of Volume III of Vyse.) FIGURE 10.

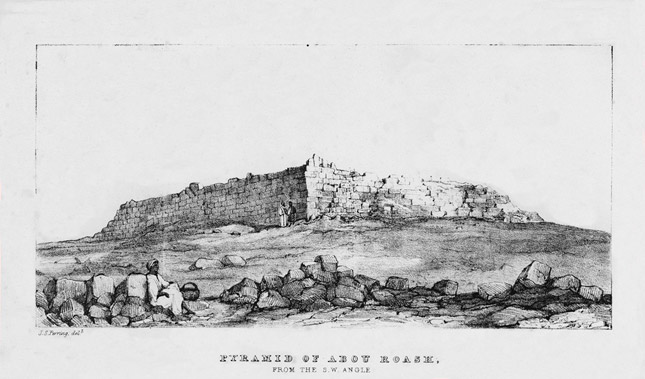

FIGURE 10. In 1840, Howard Vyse published this drawing of the so-called ‘pyramid’ of Abu Ruash seen from the south-west, as it existed in 1837. (Since that time, most of this wall has been carried away stone by stone by the Arabs and used for their own purposes.) As may be seen, nowhere was there a portion of this square wall rising more than about twelve courses of stone; the scale is given by the man standing near the corner of the wall in the centre of the picture. This wall did not go across the shaft opening to the north of this structure. Many people have concluded, wrongly in my opinion, that this was the site of an ‘unfinished pyramid’. However, there is no evidence whatever to support such a view. The fact that a sloping wall of approximately this height surrounded the vast excavated shaft (see Plate X) does not constitute evidence of a pyramid, even an ‘unfinished’ one. I believe this site to have been a meridional astronomical observatory shaft, used for checking the accuracy of the calendar, and that the similar shaft (known to date at least to the Third Dynasty king named Neferka) at Zawiyet al-Aryan, many miles to the south of here, was also used for that purpose. (This plate faces page 8 of Volume III of Vyse.) FIGURE 11.

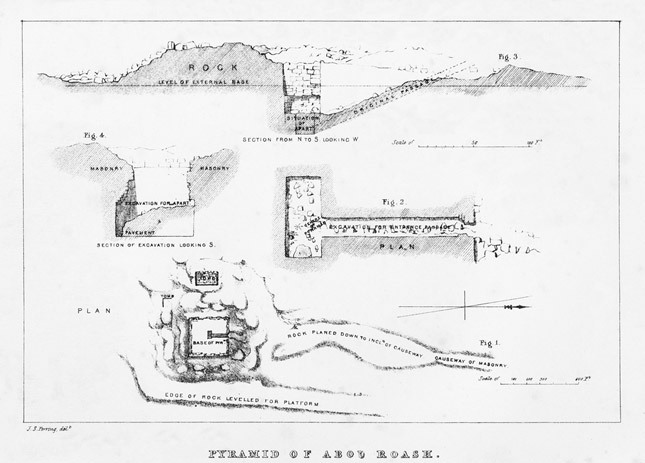

FIGURE 11. Vyse’s drawings published in 1840 showing the sections and plans of the so-called ‘pyramid’ at Abu-Ruash, which I believe to have been an astronomical observation shaft surrounded by a stone wall. The shaft is oriented precisely to the meridian, pointing north, so that the circumpolar stars of the northern sky could be observed in their meridianal culminations every night, in order to check the accuracy of the calendar. The levelled rock platform to the east of the wall could have been used for stellar and sunrise observations. This site is conveniently situated at the top of the highest hill near Memphis, and the pyramids of Giza may be seen several miles away in the distance, down below to the south, although today they tend to be considerably obscured by mist caused by the smog of Cairo. (This plate faces page 9 of Volume III of Vyse.) FIGURE 12.

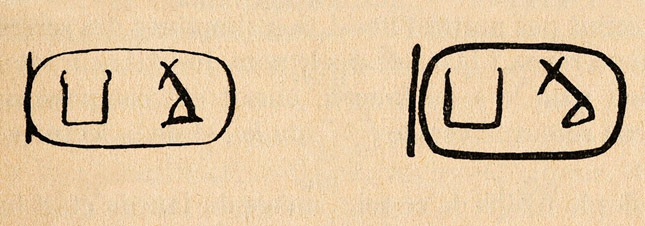

FIGURE 12. The two inscriptions of the name of the Third Dynasty King Neferka, inscribed in royal cartouches, which were found during the excavation of Zawiyet el-Aryan. These demonstrate that the site cannot possibly be of Fourth Dynasty date, as many Egyptologists erroneously insist, and for which there is absolutely no evidence. These are Figures 3 and 4 on page 305 of Jean-Philippe Lauer’s article ‘Reclassement des Rois des IIIe et IVe Dynasties Égyptiennes par l’Archéologie Monumentale’ ‘Rearranging of the Kings of the Third and Fourth Egyptian Dynasties on the Basis of the Archaeology of the Monuments’, Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres, Comptes Rendus … 1962, Paris, 1963, pp. 290-309, with a Response by Pierre Montet on pages 309-310. FIGURE 13.

FIGURE 13. Jean-Philippe Lauer’s section and plan of the exposed shaft and chamber at Abu Ruash, based upon the earlier section and plan drawings of John Perring in the 19th century. Note the precise north-south alignment of the shaft. This is Figure 1 from Jean-Philippe Lauer, ‘L’Excavation de Zaouiet el-Aryan’ (‘The Excavation of Zawiyet el-Aryan’). FIGURE 14.

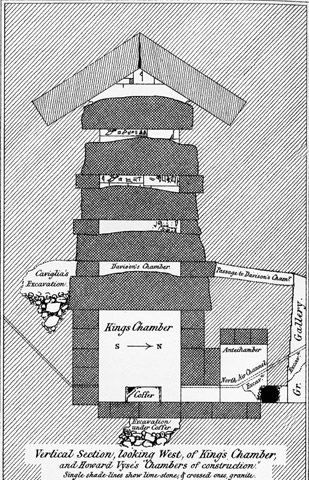

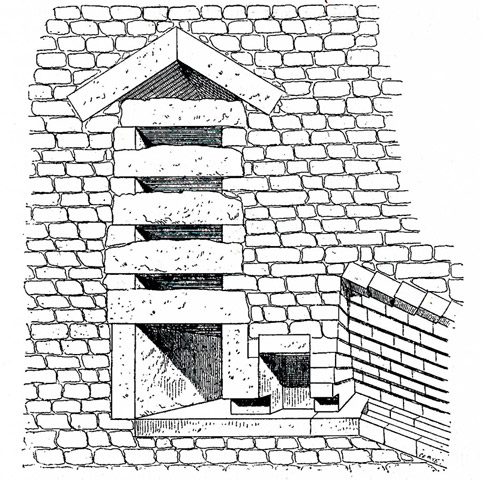

FIGURE 14. The relieving chambers over the King’s Chamber, seen in a vertical section looking west, as drawn by Charles Piazzi-Smyth and reproduced by him as Plate 14, before page 97, in Volume II of Smyth’s three-volume work, Life and Work at the Great Pyramid, Edinburgh, 1867. Smyth also shows the locations of the graffiti. It is useful also to see Smyth’s drawings of the depth of the early 19th century excavations under the coffer (these diggings are now entirely concealed, so that most people are unaware that these ever took place), and the details of Caviglia’s excavations south of Davison’s Chamber. FIGURE 15.

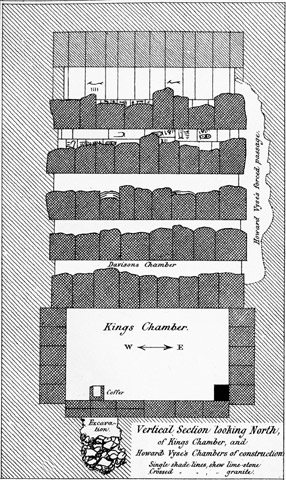

FIGURE 15. Piazzi-Smyth’s drawing of the relieving chambers above the King’s Chamber seen in a vertical section looking north, being the other half of his Plate 14. The small black square in the bottom right corner of the King’s Chamber is the entrance. FIGURE 16.

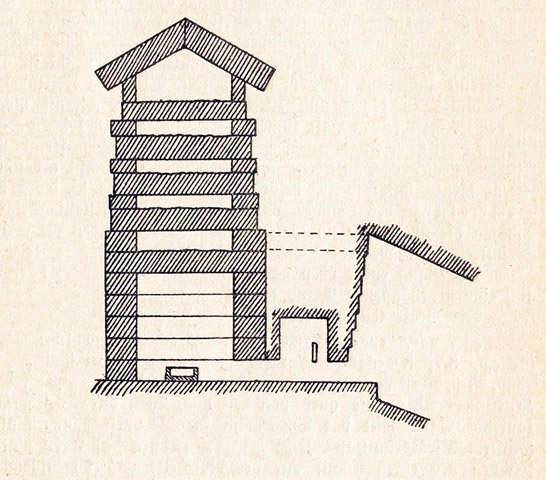

FIGURE 16. This drawing is from an obscure German pamphlet by Heinrich Hein, entitled Das Geheimnis der Grossen Pyramide (The Secret of the Great Pyramid), Zeitz, Germany, 1921, Figure 2, page 10. (I have prepared a full translation of this interesting pamphlet, and hope to publish it one day.) It is particularly useful in that it shows the connecting passage (represented by dotted lines) by which Nathaniel Davison in 1782 discovered what is known as ‘Davison’s Chamber’ inside the Great Pyramid. The structure on the left shows the King’s Chamber (with the coffer on the floor also shown) surmounted by a series of ‘relieving chambers’, the lowest of which is Davison’s Chamber. At right, the termination of the Grand Gallery is shown, just below the roof of which is the entrance to the tiny passage shown by the dots. FIGURE 17.

FIGURE 17. Longitudinal section in perspective view of the King’s Chamber and three of the ‘relieving chambers’ above it. Figure 153 on page 228 in Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez, Histoire de l’Art dans l’Antiquité (The History of Art in Antiquity), Paris, 1882, Vol. I, l’Égypte. FIGURE 18.

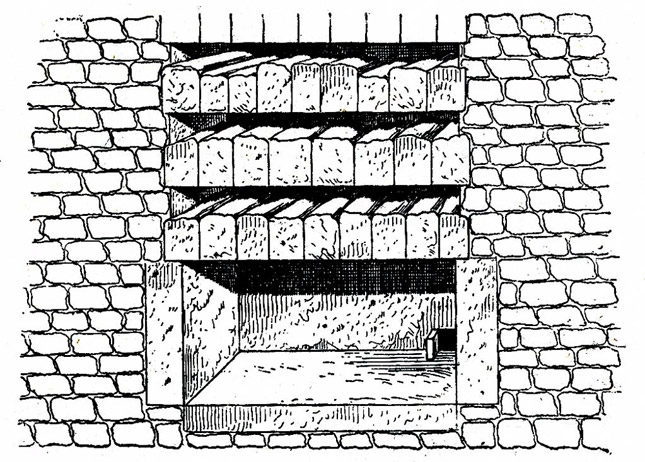

FIGURE 18. Transverse section in perspective view of the King’s Chamber with the five ‘relieving chambers’ above it, in the Great Pyramid. At right is the top end of the Grand Gallery. Figure 152 on page 227 in Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez, Histoire de l’Art dans l’Antiquité (The History of Art in Antiquity), Paris, 1882, Vol. I, l’Égypte. FIGURE 19.

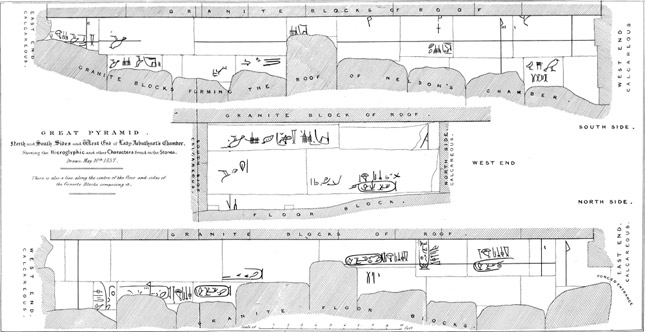

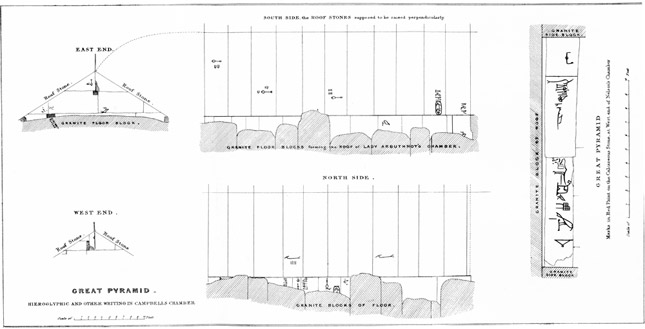

FIGURE 19. Folding plate opposite page 279, of Volume 1 of Howard Vyse, Operations Carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, 3 vols., London, 1840. FIGURE 20.

FIGURE 20. Folding plate opposite page 284, of Volume 1 of Howard Vyse, Operations Carried on at the Pyramids of Gizeh in 1837, 3 vols., London, 1840. FIGURE 21.

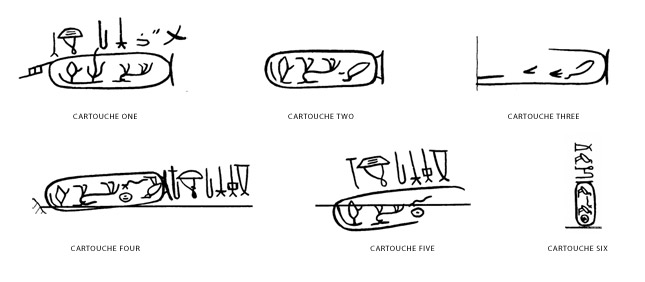

FIGURE 21. Here are the six whole cartouches which appear as graffiti in the ‘relieving chambers’ above the King’s Chamber inside the Great Pyramid, and which were forged by Howard Vyse and two of his assistants. Not one of the whole cartouches represented in these Great Pyramid graffiti is correct. Not one of them gives the name ‘Khufu’ (the Egyptian form of Cheops). Nowhere in the graffiti does the correct Egyptian hieroglyph for ‘kh’ appear. That hieroglyph is a circle with thin parallel stripes drawn across it diagonally, which is generally thought to represent a round reed sieve. When writing the name ‘Khufu’, one always begins with that and then follows with the signs for ‘u’, ‘f’, and ‘u’. The men who faked these graffiti did not understand correctly at that period in time that this was how the name of ‘Khufu’ was meant to be written. Instead, the circular hieroglyph is shown either with a dot in the centre (which was the sign for the sun, Ra or Re), with a dot and a line in the centre (which means nothing and is a sign which never existed), or with a splodge in the centre which is of indeterminate shape. When the solar hieroglyph is used in these graffiti, the reading is thus: ‘… -raf’, and is definitely not even ‘…khaf’, much less ‘khuf’. The little chicken used as a hieroglyph for ‘u’ by the Egyptians is so badly drawn that it looks more like an Egyptian vulture (which was a different hieroglyph entirely), or otherwise looks like a six year-old’s attempt to draw a fish. All of the whole cartouches found amongst these graffiti are erroneous and pathetic forgeries. FIGURE 22.

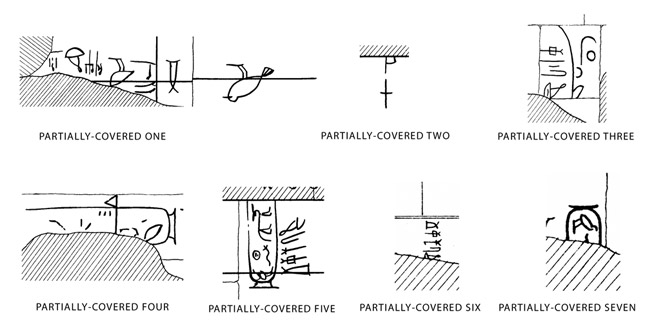

FIGURE 22. Here are the seven half-covered or partially-covered graffiti found in the ‘relieving chambers’ above the King’s Chamber inside the Great Pyramid. Once again, as with the whole cartouches, the name of ‘Khufu’ does not appear anywhere. There is one pathetic attempt to simulate it, but the hieroglyph which should have read ‘kh’ is again erroneously shown as a disc containing a horizontal line with a dot under it, which never existed as an Egyptian hieroglyph, and the chick at the end is barely even suggested, it is so badly drawn. These sketchy markings could easily have been painted up to the edge of an adjoining stone, and there is no evidence that they continue underneath. A few of the lines shown here do not even reach the edge, but stop short of it, though without inspecting the original graffiti, it is impossible to know whether this is true of the originals or is a failure of the modern artist in his copying. There is no feature of these graffiti which is in any way convincing, and all of them appear to be fakes made by Howard Vyse and his two assistants. |